"I hope it will be like a kindergarten for older people."

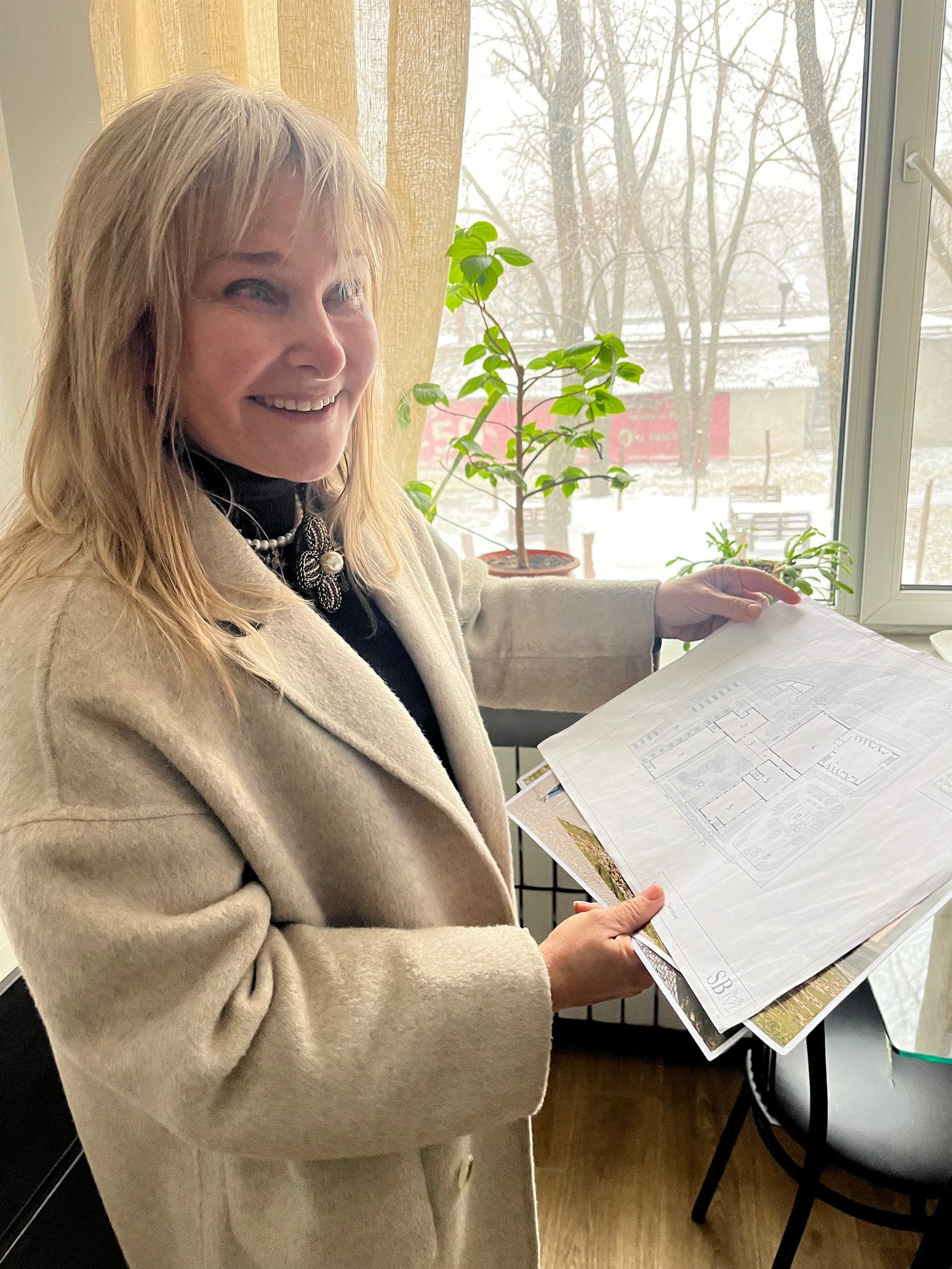

Architect Olga Kleitman's firm is one of the top in the world. But she never told me that; she talked about the elderly Ukrainians now in her care just 15 miles from the border with Russia.

KHARKIV, Ukraine — “I saw a couple falling in love here. They met here and fell in love.” If this sounds like a place you want to be, it’s 15 miles from the border with Russia. Aptly named Shelter, it’s a home opened during the full-scale invasion by world-renowned architect Olga Kleitman for Ukraine’s elderly with nowhere else to go.

Shelter is one of the main initiatives in the nonprofit organization she co-founded, Through the War. She opened Shelter after witnessing the impossibility of many families and social workers continuing to care for the elderly in their lives.

And “world-renowned” isn’t fluff in Olga’s case: Architizer named her firm, SBM Studio, the best firm in the world for public projects; and her firm is participating in this year’s über-prestigious Biennale Arte 2024.

But when I spent the day with Olga in February and again in August, we didn’t talk about her global successes as an architect. We talked about the stories of the people she cares for at Shelter — for whom war has served as bookends to their lives.

Kharkiv, a globally important city

Kharkiv is Ukraine’s second largest city. It’s a major cultural, educational, academic, scientific, transport and industrial center of Ukraine, as well as many other countries. Home to about 1.4 million people, its 38 higher-educational institutions are (normally) attended by students from around the world. It’s also where Olga received her education.

The city has always been home to Olga, whose firm designed Sarzhyn Yar, a park in Kharkiv known in architectural circles around the world.

Meeting Olga on a “normal” day in February

Ruslan Misiunia (@rysland) with Kharkiv Media Hub (@KharkivMediaHub) and I take an Uber to Shelter. When I met with the Kharkiv Media Hub team about inspiring leaders in Kharkiv, Olga was at the top of their list. Ruslan very kindly takes a day out of his busy schedule to help translate — not because he has to (the Kharkiv Media Hub team volunteers their time now, see below), but because he and his team are committed to fighting Russia’s illegal invasion by communicating the truth.

Back to our drive to Shelter. Our driver gets lost because GPS isn’t working — Ukraine’s military is scrambling the GPS signal, which they do to prevent Russia’s Shahed drones from reaching their targets. Russia launches Shahed drones and missiles on a near-daily basis at the Kharkiv region, often at civilian targets. Today is no different. (GPS scrambling is so frequent there that, on autopilot, I check the accuracy of my location when I come back to the U.S. now.) This is one of many war-related consequences that Kharkivians are forced to adjust to in their daily lives. Getting lost is obviously far from the worst.

But of course nothing about war should be normal.

After Ruslan and the driver work together to figure out where we’re going, we arrive at Shelter. It’s a nondescript three-story building with a gray and light brown exterior that blends into the landscape around it.

Olga greets us outside with sun in her eyes and energy that defies the lack of sleep she’s had for the past two-plus years. Like a lot of Ukrainians now, she’s exhausted and sees no end of Russia’s invasion in sight. But she lights up when she says we must see her new chickens as the first stop.

Olga’s chickens, Shelter’s residents and where the help comes from

Olga excitedly escorts Rulsan and me through the hallway en route to the back door. We meet Christian on our way, a rehabilitative specialist from Chicago who started volunteering at the home right after it opened — right after the full-scale invasion began. He’s helping several residents walk again, several of whom were bedridden because of the invasion and the lack of proper help it brought or exacerbated — such as Mariia. She hadn’t walked in nearly two years before Christian began working with her at Shelter.

We head to the hall and get close to the back door when one of the female residents stops us and starts chatting (flirting) with Ruslan. The woman seems happy, thanks in part to Ruslan’s conversation with her — and because there’s joy here, despite everything the residents have been through, who are some of the most vulnerable people in Putin’s genocidal, illegal invasion and occupation of Ukraine. Ukrainians aged 60 and over account for a quarter of the country’s population but a third of the deaths directly caused by the full-scale invasion.

We continue to follow Olga, finally making it out the back door to see the chickens, who live at the back of the seven-acre property. Olga’s birthday was in February, a few days before our visit — and the chickens were a birthday gift. She jokes that the chickens were supposed to be for the home, but that they’re really hers. (She calls them her “toys” as translated, but in context she’s calling them her little friends.) They’re in a temporary house for now and will be in a permanent place on the property soon. I have no doubt that it will be a chicken retreat and spa based on how much they mean to her. (August update: The chickens now have duck and dog friends, in an effort to provide emotional support to the residents and a home to the two formerly stray dogs.)

Olga has earned her chickens. She and her husband spent their own money to open the center, and Olga pays the nurses and other site staff from her own pocket.

She relies on aid from Ukraine, the U.S., Taiwan and other countries. Fellow Ukrainians contribute a significant amount of that aid.

People from all over the world volunteer here, too — people from Ukraine, France, Poland, New Zealand and the U.S. to name a few.

Olga provides a home for as many elderly people with nowhere else to go as she can. Before we go back inside, Ruslan whispers to me that a man sitting on the patio is “Kharkiv’s most famous crazy person.” He’s sitting quietly outside, staring out at the falling snow. He seems quite happy here — and calmer, Ruslan says.

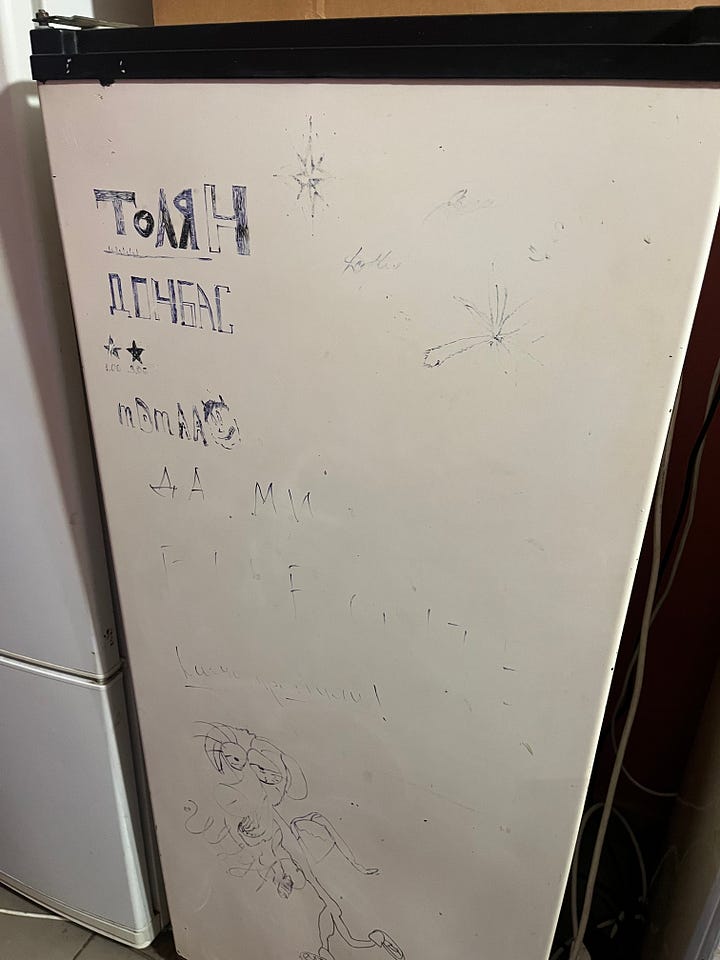

Back inside, we walk through a food storage area and pass a refrigerator on our way upstairs that says, “From Tony, from Donbas” on the door. Olga says the refrigerator escaped Russian occupation, but she’s not sure about Tony. (Donbas is in eastern Ukraine and mostly occupied by Russia right now — illegally invaded in 2014, when Putin realized the world was turning away.)

The food storage area includes a small but homey area for residents to gather with each other. A few of the female residents are watching TV and nod to us as we walk by. Olga points to the half-empty shelves and tells us that most of the food is donated by Ukrainians, who give whatever potatoes and other necessities they can spare. But “spare” isn’t really the right word, because it’s not as though they’re giving away excess: They themselves also need what they give.

Immediate needs

Shelter has two nurses who take turns to ensure 24/7 coverage. Olga also has an agreement with a local hospital from which doctors visit every week to help with medical recommendations. Everyone is overtasked.

One of the new residents loses consciousness all the time. She was brought to the home by her son, who joined Ukraine’s armed forces and can therefore no longer care for her. It was a painful decision in a war where there are no easy choices about the future. One of my Ukrainian friends told me that he and every Ukrainian he knows feel they are all living temporary lives. That statement runs through my head as Olga tells me about this mother and her son.

But Olga, her husband and Shelter’s donors and volunteers are doing their best to plan for an uncertain future.

Olga’s sister lives in Seattle and works for Microsoft. She donates what she can to help the home. Her sister also helped set up a matching program with Microsoft, in which Microsoft matches whatever their employees give (through Benevity).

One immediate need Olga was able to address since I first met her in February is an elevator to the third floor. The third floor was unusable for residents because it required too many flights of stairs for them to walk, and many can’t even make it to the second floor.

Now, because Russia significantly destroyed Ukraine’s energy infrastructure this spring, the looming winter weighs on Olga. Winter in Kharkiv often dips below zero in both Fahrenheit and Celsius from December to February. January is usually the coldest month, when many residents become depressed because they can’t go outside. Olga is trying to secure funds to enclose a large porch, so that residents can feel any sun the city receives during what will be another war-torn winter. She says this is a top priority because the residents’ emotional and mental health is a top priority.

Shelter is also in dire need of narrower beds because the rooms are narrow and long. Multiple people live in each room, a necessity to take care of the daunting number of elderly residents who would otherwise fall through the cracks of Russia’s invasion. But the beds they have right now don’t make efficient use of the rooms, which therefore limits the number of people they can provide housing for.

And the immediate need in the Kharkiv region is significant: There are only eight elderly care homes in the region, which are government-run and have a total capacity for 1,000 residents. They’re all full. “It’s a huge problem,” Olga says. She also explains that people move in for a bit and then move out of the government facilities, creating even more uncertainty at a time in their lives when they thought they would be in their own homes spending time with their loved ones. In Ukraine, like many European countries, elderly family members are generally cared for by their families. Russia’s invasion changed that.

Russia’s invasion also changed circumstances for the elderly who were previously able to live on their own.

Yuriy

Immediately after we meet Yuriy, a resident at the home, he invites me to his apartment “when it’s fixed, when everything will be okay,” he says.

Ruslan translates, saying: “Unfortunately, [Yuriy] cannot walk, so his activities here are limited. But he has a radio. He says he listens what those Russian bastards are doing, and he’s waiting … because this war ruined the cycle of life and all the rhythm to it.”

Yuriy’s a retired driver in his late 70s to early 80s. (I was caught up in his inviting warmth and charm and forgot to ask his age.) He was living on his own and had a stroke right before the full-scale invasion. No longer able to walk and without local family, he paid a social worker to look after him. Then Russia hit his apartment building, twice.

His apartment is in Saltivka, a district on the north side of the city. Saltivka was hit especially hard by Russia early in the full-scale invasion because it was on the road from Russia directly into Kharkiv (and less than 15 miles from the border).

When Russian troops entered the outskirts of Saltivka, Yuriy’s apartment building was hit with a missile. He continued to live in his apartment until Russian troops hit his building the second time. The stress from the direct hits and his stroke was too much, and his vision worsened. Then the social worker he hired stopped coming. He heard about Olga’s home and decided to call.

“It's not good to be at home. And it's not good to be a guest,” he says. But he’s very grateful for Olga and the team here. “Everything that a person needs is here … thanks to the volunteers.”

Yuriy’s waiting to return to his apartment, and his building was undergoing repairs at the time of our interview. I’m eagerly waiting for his invite.

August updates and big plans

When Olga and I meet again in August, she tells me that she’s been able to make some more improvements at Shelter. In addition to installing the elevator and getting the ducks and dogs, she was able to fit the home with handicap-accessible features in the bathroom. Now, residents feel more independent and the nurses have some relief. The care she takes in thinking through how every donation can be maximized is evident.

She also hired a social worker, whom she also pays from her own pocket. She says what keeps her up at night is worrying about how she’ll continue to pay the staff at Shelter (as well as the 10 architects and five engineers working at SBM Studio).

And Olga has big plans. She again lights up when she shows me plans for three new buildings, which she says will be built “sustainably” and to European Union standards. (Ukraine is making rapid changes across the country to conform to European Union standards. It’s a massive effort.)

Longer term, Olga wants to make the home “like a community. I hope it will have a restaurant, a bar and a library. I hope it will be like a kindergarten for older people,” she says.

"My dream is to make the home nice enough that my husband and I want to live here."

You can help

If you’d like to help Olga with items such as windows for the porch enclosure, new beds and food and other supplies, visit Shelter’s organization, Through the War: https://throughthewar.org/shelter.

You can also contact me if you’d like to help Olga with longer-term investment needs, and I’ll put you in touch with Olga.

Kharkiv Media Hub

A BIG thank you to the Kharkiv Media Hub and especially to Ruslan Misiunia for taking the time out of his schedule at the hub to help translate.

The Kharkiv Media Hub’s institutional funding dried up in December 2023, but they continue to work tirelessly on a volunteer basis to fight Russia’s full-scale invasion by communicating the truth about Ukraine, the invasion and the nation’s remarkable people like Olga.

So far, they’ve connected more than 1,200 journalists to the stories that matter in Ukraine. Additionally, they hold press and educational briefings and produce content to educate the world about what’s really happening in Russia’s genocidal invasion of its sovereign (and older) neighbor. And when Russia’s attacks became particularly severe again this spring (2024) in the Kharkiv region, they risked their lives to evacuate civilians and document Russia’s war crimes themselves.

You can help them via PayPal: kharkiv.mediahub@gmail.com